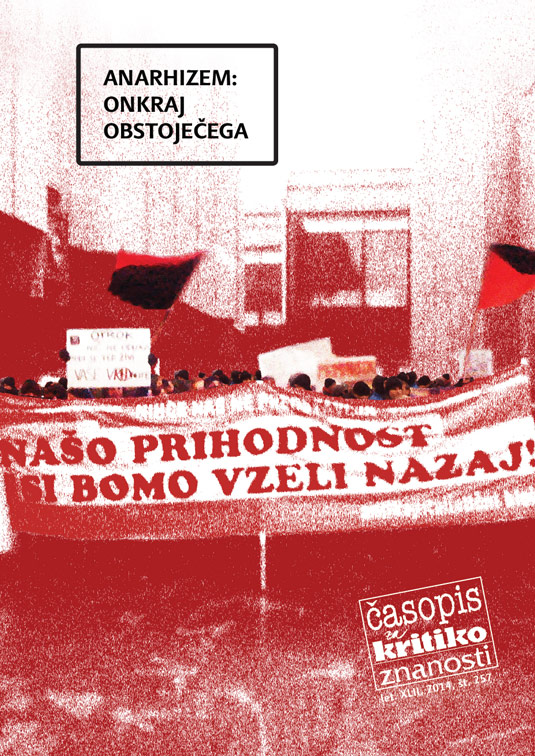

Naslov uvodnika v pričujočo tematsko številko Časopisa za kritiko znanosti o anarhizmu se je leta 2009 pojavil na platnici prve številke anarhističnega časopisa Avtonomija, ki ga je izdajala Federacija za anarhistično organiziranje iz Slovenije. V njihovih analizah sistema, bede in izkoriščanja na eni strani ter iskanja alternativ na drugi so anticipirali silovite eksplozije, ki so tedaj, na začetku gospodarske krize, že dolgo pretresale svet, a so bili le redki zmožni razmišljati o njih tudi v tukajšnjem prostoru. Kar je takrat (in morda še danes) za nekatere zvenelo kot prenapihnjene sanjarije, fetišizacija in ideal politično nedorasle, marginalne in naivne skupine anarhistov, se je konec leta 2012 v Mariboru in nato bliskovito po vsej državi manifestiralo na ulicah, trgih, v vaseh in vseh narečjih.

Ni se zgodilo zaradi njih in zagotovo bi se tudi brez njih. A anarhisti so bili poleg in so na dogajanje vplivali. Tako kot v številnih uporih pred vstajami in bodo (verjetno) tudi v številnih po njej. Njihov realni vpliv na širše družbeno dogajanje lahko merimo skozi prizmo številk – tu bodo anarhistke in anarhisti vedno izgubili. Njihov uspeh lahko merimo tudi skozi preprosto ugotovitev, da po šestih mesecih na ulicah vstaje niso prinesle ne brezrazredne družbe, ne odprave kapitalizma, ne konca hierarhij in dominacije. In jih spet zadovoljno pomirjeni odložimo na polico subkultur, utopij ali romantičnih novel. Lahko pa optiko obrnemo in skozi daljše obdobje vstaje, proteste, družbena vrenja in anarhistično delovanje znotraj njih razumemo skozi prizmo prelomov, mnogoterosti zmožnega, trenutkov radostnega upora in eksplozije časa, po kateri nič več ni enako, predvsem pa ne linearno.

The article presents an outline of the development and the impact of the anarchist thought in Slovenia from the 19th century until today. It describes a series of libertarian practices, from mass workers’ and students’ movements to more individualistic attempts of revolutionizing the everyday life. It recognises anarchism as a heterogeneous set of diverse, yet sometimes contradictory, ideas and practices, characterized by a continuous struggle for liberation from the shackles of hierarchies, authorities, and capitalism. Anarchist ideas were introduced to the Slovenian territory simultaneously with the European sprawl of radical workers’ movement in the 19th century. The rise of these ideas within workers’ circles was followed by repression that culminated in the Klagenfurt/Celovec trials, resulting in anarchism temporarily losing its strength. At the turn of the century, anarchism was spread mostly by artistic circles, whereas during both World Wars Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War (španski borci) became acquainted with it abroad. During the sixties with the student movement, and especially in the eighties with punk, anarchism was present in squats, communes, and within occupied public spaces. At the turn of the 21st century, it flourished once again. The chronology of the development of this political thought, often marginalized in Slovenian historiography, shows that anarchism as a radical critique of society was always faced with severe repression. By revealing the historical flow of anarchism, the article offers key coordinates for further research on the topic.

This is the translation of the text by Johann Most, German-speaking anarchist and agitator, who was an avid supporter of the anarchist organizing and propaganda by deed. We decided to translate it because the work and ideas of Johann Most were one of the biggest influences on anarchist organizing in the Slovenian-speaking area in the 19th century. In the text, Most pummels the concept of waiting for the right moment to resist and fight for freedom. He analyzes different factors that contribute to the general apathy and being susceptible to manipulation, and prevent the creation of the political space for self-emancipation and self-organization. Therefore, he attacks theoreticians and the Church, the latter because it is more fond of advocating empty promises and waiting for utopia that is yet to come, than resistance. He is also critical of politicians of any kind. He is particularly harsh towards social democrats and socialists, who in his opinion not only advocate freedom only after assuming political power, but mostly because they strip people of the validity for self-analysis and self-determination, and promote the avant-gardist position of knowledge and strategy of resistance, all the while pretending to be “on their side.” This position in particular still resonates with the existing contemporary political parties of (a more) socialist background. In the last few years, they are emerging in the form of a party-movement, and yet they still use the identical policy of waiting, which, according to Most, destroys all potential for the realization of full freedom.

In addition to providing the chronology of the most important episodes of anarchist activities in Slovenia in the last 15 years, the article closely examines the forms and methods of political organization and action that led to the creation of the Federation for Anarchist Organization. It outlines the ideological and theoretical underpinnings of anarchism in Slovenia. The latter has enabled the development and continuity of activities in various social initiatives and movements, of which anarchists were sometimes initiators and sometimes supporters, but in any case their work was always based on anarchist ideas and principles. This practice placed anarchism on the political map as a distinct political force in social movements. Despite the fact that anarchism is internally heterogeneous and full of different views and flows, it appears to be unified on the outside.

The article contains the edited transcription of the discussion on the crisis of representation, held in the anarchist social centre [A]-Infoshop on Metelkova, on February 21st 2013, and entitled Beyond Representation. It was an event in the debate series Thinking the Impossible, which arose as one of the initiatives of the Anticapitalist Bloc, which was created within the heat of uprisings, and brought together antiauthoritarian, antifascist, anarchist, radical, emancipatory, and autonomous collectives, initiatives and individuals. The debate circle addresses contemporary issues of the struggle against capitalism in a horizontal manner. The transcription is accompanied by a brief theoretical reflection on some of the most pressing issues of today: the crisis of the concept of representation, crisis of the concept of (liberal, consensual, parliamentarian) democracy as a regulator between law and economy, crisis of the concept of the state as a model enabling violence of the system. In addition to the claim that none of the above concepts can represent real politics as an idea of radical equality since they are based on the idea of inequality, exploitation and domination, the article focuses on several horizontal, autonomous and solidarity practices that were opening spaces of opportunity of the impossible as a true politics of emancipation during the uprisings in Slovenia in 2012/2013.

In the article, the author discusses the need of the working class to organize itself in radical trade union networks, in order to surpass traditionalist reformist trade unions and their bureaucratic constraints and rigidity. Based on his experience with wildcat strikes and radical autonomous workers’ organizations, and contacts with Slovenian unions, the author defines key differences between methods of organizing within traditional trade unions and anarcho-syndicates. The article is focused mainly on (non-)hierarchical relationships between the base and decision-makers, the ways and methods of the worker’s struggle, and the ability of overcoming individual issues of the syndicalist struggle. The author finds that the main problems within traditional trade unions lie in the alienated decision-making process, representation, and the fact that their actions are limited to fighting for rights within the existing system. He recognizes radical syndicalism as a method of establishing economic self-organized communities, acting according to the principles of solidarity, autonomy, internationalism, direct democracy and direct action, and strive for the reproduction of radical syndicalist knowledge and greater independence and freedom of the people from free trade market economy and from the technological production process, and the concept of work itself. The article also deals with the emerging challenges of capitalism, with the equal rights struggle of migrants and new forms of syndicalism that would include precarious workers. By researching the basic differences in the ways of organizing the syndicalist struggle, the article wishes to contribute to its improvement and radicalization.

Since the mid-1990s, CrimethInc. has been one of the most prolific and ambitious anarchist projects in North America. Participants have crisscrossed the world for countless tours and actions; produced books, magazines, and other publications, including 650,000 copies of their debut Fighting for Our Lives. The collective has been to Slovenia several times, therefore partial translation of their book Work directly resonates collective discussions of the Slovene-speaking anarchist movement and CrimethInc. In the text entitled Resistance they explore possibilities of revolutionizing our lives on the everyday level. They emphasize that anyone and everywhere can resist, as long as this resistance remains inherent to the needs of every individual. After the initial analysis of the system around us, authors reject reformism as a productive form of engagement in the struggle for a radical transformation of society. The only way to combat recuperation of alternative practices is, in their opinion, a constant struggle against and beyond the existent. They understand resistance as a long-term process of continuous breaks, non-linear advances and retreats, where the main component of every revolutionary strategy remains a constant revolutionizing of the tactics. The text is therefore a mixture of analyses of the system and of the resistance, as well as a field guide through the new territories of struggle.

The article deals with research on anarchism through the analysis of utopias. The latter offer us a possibility to look through the prism of binary division on social and individualist anarchist currents, and therefore observe variety and diversity of anarchisms. Even though many attempts, mainly from classical anarchist thinkers, were made to avoid the label of utopian, utopias had an important impact on anarchist praxis-thought, either as a motivation for resistance or as a desire to experiment with an ideal society here and now. And it is precisely this point where various interpretations which cause many contradictions between diverse specters of anarchisms occur. But utopias also supplement, constantly redefine and question idea of anarchism and therefore build it in a vivid, changing thought of plurality, diversity and spontaneity. Through understanding of utopias, heterotopias and political theories, we will search the reasons for divisions between praxis and theory that, despite many efforts to overcome them, still manifest themselves through different approaches on the quest for freedom. Diverse revolts against hierarchies and restraints of power, which encompass all specters of people’s lives, are quite different, but they always cross at the intersections that are marked with principles of antiauthoritarianism, mutual aid, solidarity and self-organization. Utopias in the revolts remain the place of infinite imagination, creativity and the unstoppable desire for freedom.

This article is a direct address to the reader not to passively study but rather actively create a theory. The text does not conform to the norms of objectivity, but is rather trying to overcome theoretical and practical alienation from self, life and struggle. The author tries to reveal the traps of linear conceptions of time and the development of struggle. He analyzes how the limitations of thinking and acting occur within the predominantly Marxist, but also anarchist theory, when it is alienated from its own needs. In the first part of the text he therefore sharply rejects any sort of frames and programmes, which would lead activists towards waiting instead of acting. He also marks the danger of creating hierarchy when it comes to struggles, or reducing them to an issue of the economic sphere. Later on, he analyzes the concepts of “the existing” and “civilization”, as understood by insurrectionalist tendencies within anarchism in the case of the first concept and within anarcho-primitivism in the case of the second. Both terms describe a static condition and are, in reality, manifested as a limitation in the construction of a world beyond capitalism, alienation, hierarchy, and domination. The author puts the struggle; the struggle for life, action and feelings against these two concepts. The article does not aspire to give answers, but rather to pose questions. Therefore, it must be understood as an open attempt of building theory from the movement, without trying to set itself to the position of knowledge.

The author deals with the relation between anthropology and anarchism, which is understood as a relation of mutual appropriations. The aim of the text is to contribute to the discussions on the relation between anthropology and anarchism, by focusing on the political potential of anthropology as it is used by anarchists themselves, and by stressing the anthropological character of anarchist social relations. In the first part, the author considers the possible relations between anthropology as a discipline and anarchism as theory and practice of radical social transformation. Although the relation can be problematic, the author argues that anthropology carries great potential in the theoretical substantiation of social relationships, which are not organized by the market or the state. Anthropology enables us a way to de-naturalize the dominant way of living and demonstrates a heterogeneity of possible futures. The author regards anarchism as a mode of theoretical production »from below«, which generalizes micro-political aspects of revolutionary transformation. In the second part, the author deals with anarcho-primitivism as a strain of anarchism that uses anthropological knowledge most actively in the advocacy of »primitive anarchy«. He discusses the challenge of anarcho-primitivism to traditional forms of anarchism, such as anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism. In the last part, the author draws on Graeber’s conceptualization of communism, in order to substantiate the anthropological character of anarchism. According to Graeber, we can regard communism, on the one hand, as social totality while, on the other hand, we can also understand communism as »the foundation of all human sociability.« The author argues that it is also possible to understand anarchism as the key part of human sociability, if we take into account our everyday experiences of horizontal social relations, mutual aid and organization of social relations in the absence of authority.

The essay aims to rethink terms like realism, imagination, alienation, bureaucracy, revolution itself. It was conceived on the basis of some six years of involvement with the alternative globalization movement and particularly with its most radical, anarchist, direct action-oriented elements. It is a kind of a preliminary theoretical report. The author asks, among other things, why is it these terms, which for most of us seem to evoke long-since forgotten debates of the 1960s, still resonate in those circles? Why is it that the idea of any radical social transformation so often seems “unrealistic”? What does revolution mean once one no longer expects a single, cataclysmic break with past structures of oppression?

In the translation of this essay, the reader will first find a short list of key achievements, contradictions and failures of the feminist movement throughout its history. The study begins with the key issue: what can anarchists learn and introduce into their struggle from these processes. Thus, we become familiar with the critique of reductionist politics, which puts (only) the anticapitalist struggle in the primary position of every resistance, with the assumption that its destruction will necessarily do away with all other forms of domination in society. They do not avoid the fact that such moments of reductionism also occur within the anarchist movement itself. They also consider as inadequate all forms of feminism that are based on female identity, since these lead towards identity politics. Finally, they reject liberal feminism that seeks a solution for gender domination within the capitalist system. As a field of potential inspiration for future anarcho-feminist struggles, the authors suggest the intersectionality theory, which studies the simultaneous effect of different domination factors: gender, race, social exclusion, and more.

Schmidt's and van der Walt's text is taken from their book Black Flame, which was published by AK Press in 2009. For the present edition of the Journal for the Critique of Science, third chapter was translated. The broad anarchist tradition was profoundly influenced by both Proudon and Marx, but did its best to eschew determinism, teleological views of history, economic reductionism, and functionalism. The key elements of an anarchist social analysis in the text have emerged in a schematic form. Anarchist analysis, in its most sophisticated form, centres on the notion that class is a principal feature of modern society and thus that class analysis must be key to understanding society. At the same time, it takes ideas, motives and actions seriously, and avoids monistic models of society. In rejecting economic determinism and stressing the importance of subjectivity, this analysis does not replace one form of determinism with another.

In the text, we are faced with the relationship between anarchism and Marxism, a process that extends in both theoretical as well as practical traditions of these two directions from the 19th century onwards. Relying on the analysis of classical texts’ thinkers of anarchism and Marxism, we are interested more in the generality of theme and wider fields disagreements than in the actual conflicts. In doing so, we pay special attention to certain essential moments of these texts, which are again and again repeated in the afore-mentioned relationship, and which, with in-depth analysis, also allow a better understanding of the current social practices. We begin by examining the basic concepts of Marxist and anarchist theories, while touching upon particular objectives, methods and our own methodological understandings of social relations. Subsequently, we move on to different aspects of the class understanding of these differences, following a clearer definition of political issues. These include dilemmas about authority, the state and political organization. We primarily explain the role and importance that these concepts and their modes of connectivity take in different theoretical models. In the conclusion, we aim to show the total foundation of these contradictions and conflicts, which is reflected in particular in relation to a different understanding of regularity, and thus to a different understanding of management in production. In doing so, we want to show that there is a political position inherent to class struggle.

The author of this translated text is one of the key anarchist historians of the 20th century. Despite the fact that the text was written following the fervor of May ‘68, it resonates in many aspects the discussions within the uprisings against capitalism, austerity, and corruption that have been making the world tremble over the last few years. The concept of spontaneity, as understood by Marxists and anarchists, is at the forefront of the text. If Marxists either completely overlooked spontaneity (for example in Marx) or negated it (in later Marxists schools of thought), anarchists were developing this concept since Bakunin. Anarchists understood the spontaneity of resistance in the context of social movements as a result of the intensifying inner contradictions within capitalism and the consequent rise of dissatisfaction among people. On the other hand, they did not reject anarchist organization, but rather saw it as something necessary. Marxists, meanwhile, insisted that class consciousness that can initiate self-activation of masses can only be produced by the actions of an avant-garde party. Rosa Luxemburg was the first Marxist to take on a more open approach to the concept of spontaneity, but even she did not trust the spontaneity of the people, seeing it as too unpredictable. That is the point where this text opens the key issue: in today’s situation, how can we understand the concept of spontaneity on one hand, and anarchist organization on the other? How can we understand the relationship between them? Above all, we must ask ourselves what the absence of the avant-garde (whether in the form of a political party or socialist avant-garde) means in the context of developing autonomous perspectives of the struggle against and beyond capitalism.

This translation of the anarchist, translator and author Gabriel Kuhn’s text is a practical guide to postanarchism and its conceptual differences with post-Marxism. Over the last decade, postanarchism as a combination of classic anarchist authors and poststructuralist theory became more and more present in the field of academic research. At the same time, numerous critical voices have been raised against it. Anarchism, in the opinion of authors who consider themselves close to the concept of postanarchism, believe that anarchism is too centered in the 19th century thought, and therefore try to reestablish anarchism as the most critical form of humanism. Kuhn researches the origins of this thought and the works of key authors, concentrating especially on the question how (if at all) poststructuralism can influence the development of anarchism in the future. He centers his analysis on the work of Gilles Deleuze. The author also critiques postanarchism, especially in the context of oversimplified interpretations of classical anarchist thought, and warns about the dangers of dismissing all etiquettes and identities, while at the same time being aware of traps of identity politics.

Saul Newman is considered the first to use the term postanarchism. In this translation of his text, the author, drawing on his studies of the characteristics of social movements in the first years of the 21st century, rethinks the move away from the Marxist concepts towards the anarchist concepts of struggle. He sees the radical critique of representation, the denial of the state and all forms of institutional politics, and doubt of the classical Marxist understanding of class, as the main characteristics of these new movements. He especially emphasizes that the commitment to classic emancipatory ideals and freedom continues in these movements. Even though he acknowledges that anarchists do not ignite all these movements, he recognizes the anarchist resonances in them. Therefore, he thinks it is vital, if we want to understand these movements, that we study anarchism in greater detail. Newman understands anarchism as a concept that urgently needs a new wave of innovation to move away from what he considers its positivistic past. Therefore, he suggests combining it with poststructuralist theory, at least with authors that Newman believes to be, whether they admit it or not, fueled by antiauthoritarian or anarchist principles.

GRAEBER, David (2013): Fragmenti anarhistične antropologije. Ljubljana, Založba /*cf.

V prvem stavku spremne besede k Fragmentom anarhistične antropologije Darij Zadnikar Graeberjevo delo opiše kot provokativno-inspirativni pamflet. Težko bi na bolj zgoščeni način strnili bralčeve občutke ob prebiranju te »vrste misli, osnutkov potencialnih teorij in kratkih manifestov« (ibid: 87).

David Graeber ni le radikalen antropolog in anarhist, aktiven v številnih bojih. Čeprav je širši javnosti najbolj znan po svoji aktivni vlogi pri gibanju Occupy Wall Street, še pred tem pa po analizi taktike črnega bloka v alterglobalizacijskem gibanju, ga vedno bolj spoznavamo tudi kot univerzitetnega predavatelja. Zato ne preseneča, da je prvo vprašanje, ki si ga v Fragmentih zastavi »Zakaj je na univerzi tako malo anarhistov?« (ibid: 8). Da bi odgovoril na to vprašanje, poskuša nizati fragmente anarhistične teorije, ki je še ni, a se hkrati v delčkih pred nami izrisuje, postaja.

GELDERLOOS, Peter (2013): The Failure of Nonviolence: From Arab Spring to Occupy. Active Distribution: London.

Najnovejša knjiga anarhista in dolgoletnega aktivista Petra Gelderloosa The Failure of Nonviolence: From the Arab Spring to Occupy ponovno obudi nenehne polemike v družbenih gibanjih o (ne)nasilju, s katero se je Gelderloos že spopadal v leta 2005 izdani knjigi How Nonviolence Is Protecting The State? Avtor v polemiko vstopa s svojstvenim in svežim pristopom v razumevanju in interpretaciji nasilja in njegovega navideznega nasprotja nenasilja in pacifizma. Svoje argumente črpa iz izkušenj alterglobalizacijskega gibanja, ki je bilo v času njegove prve knjige o tej temi že v zatonu. Že takrat je nenasilje označil za neučinkovito, rasistično, avtoritarno, patriarhalno, taktično in strateško podrejeno ter zmotno, ob tem pa želel spodbuditi vključevanje v družbena gibanja skozi prizmo raznolikih taktik (diversity of tactics).