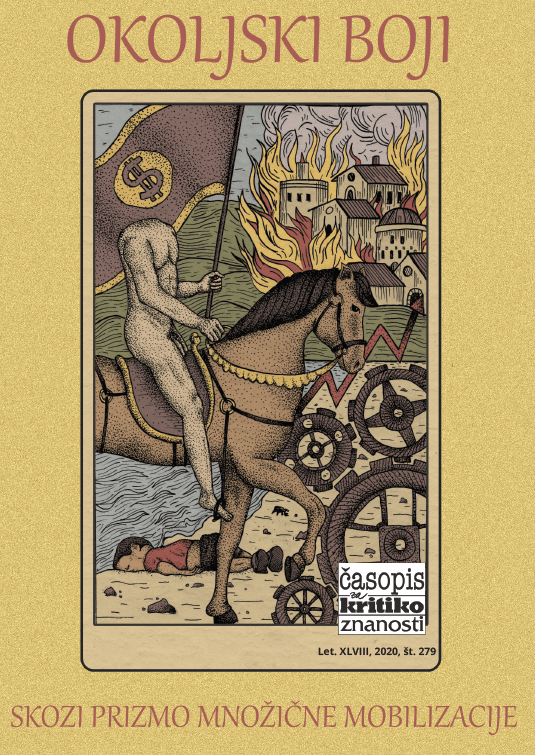

Novo številko Časopisa za kritiko znanosti, domišljijo in novo antropologijo smo zasnovali v kontekstu izjemne planetarne mobilizacije mladih za podnebno pravičnost. Šolske stavke, ki jih je navdihnila Greta Thunberg, so zavedanje o resnosti podnebne krize prenesle iz ozkih okoljevarstvenih in znanstvenih krogov ter iz globalnega pregrevanja naredile prvovrstno globalno politično temo. Gibanje se je dobro zakoreninilo tudi v Sloveniji, kjer je veter mobilizacije mladih za podnebno pravičnost končno razpihal postano politično ozračje, ki ga je proizvedla agresivna desničarska reakcija na globalne emancipatorne boje, ki so se pojavili po izbruhu finančne krize leta 2008 ter se manifestirali v arabskih pomladih in globalnem gibanju okupacij trgov v letih 2012 in 2013 ter v poletju migracij leta 2015. Eno od izhodiščnih vprašanj, ki smo si jih zastavili ob snovanju tematske številke, se je dotikalo potenciala novih ekoloških gibanj, da sprožijo procese politične rekompozicije globalnih družbenih gibanj ter uglasijo tradicije emancipatornih in osvobodilnih gibanj z mobilizacijo proti uničenju same zmožnosti Zemlje, da podpira življenje. V planetarni mobilizaciji za odločno ukrepanje proti podnebnim spremembam smo tako videli obet nastanka nove paradigme sobivanja ter ekonomskega, družbenega in političnega organiziranja.

The author introduces us to the main ideas and theses of ecofeminism and compares it to other directions in social ecology. She emphasizes the differences in valuating recognized, productivist labor on one side, and non-recognized, metaindustrial labor of women, peasants, indigenous peoples and similar groups on the other side. The author shows that current paradigms create eco-systemic and embodied debt and calls for redirection into a regenerative and reproductive economy, which is also the focus of ecofeminist thought. The text is a translation of the author's contribution to the Routledge Handbook of Ecological Econmics (Routledge, 2017).

The article goes against conventional wisdom by presenting Karl Marx as a lucid environmental thinker. In the first part, primitive accumulation is defined as a violent process through which human beings were separated from the natural conditions of their existence and production. Consequently, these natural conditions are no longer perceived by people as their own inorganic body. Connected to this is the emergence of an irreparable metabolic rift between society and nature stemming from the contradictions between capitalist and natural laws. In the second part, the author explains Marx‘s notion of nature being a free gift to capital – nature only directly affects the production of use value and not the production of value. Nevertheless, nature has many important indirect effects on value – nature performs functions that are free of charge for capital, it serves as a material substrate of value, stimulates additional absorption of surplus labour, increases labour productivity without increasing the value of manufactured goods, etc. In the third part, the author focuses on the key role of money in the abstraction from natural and social dimensions of use value and the subsequent absolute substitutability and purchasability of nature. Related to this are the capital processes of the fragmentation and homogenization of nature and labour, or more broadly, their real and formal subsumption under capital. In the last the article underlines the basic contradiction between capital’s urgent need for infinite growth and the finiteness of the planet. This contradiction is unfolding in the current environmental breakdown. As a footnote, the author also touches upon various insights into humanity’s future coexistence with nature.

“Green New Deal versus Degrowth”: Placing the Discussion in its Historical and Epistemological Context

(

In the article, the author places the “Green New Deal versus Degrowth” discussion in its broader historical and epistemological context. The article takes Robert Pollin’s 2018 discussion De-growth VS A Green New Deal as its starting point, and presents it alongside a series of (direct) responses from “degrowthers” that followed mainly in 2019. In showcasing the discussion, the author first focuses on the issue of “green growth” and, on a related note, on the (im)possibility of the absolute decoupling of GDP growth from material throughput and carbon emissions, which is an issue that has become the focal point of the “Green New Deal versus Degrowth” debate. The author proceeds to link the current discussions to the differences between (neoclassical) environmental economics, ecological economics and bioeconomics, with the aim of showing the essential paradigmatic distinction between the green new deal and degrowth. Against this background, the author concludes by highlighting a selection of epistemological questions that remain unthematized in Pollin’s discussion. These questions are highly important for understanding the differences between the green new deal and degrowth. The article includes an appendix that outlines environmental management and its impact on environmental thinking in economics, which the author problematizes from the point of view of the critical management paradigm.

Half a century has passed since the publication of the Limits to growth report, in which a team of researchers came to the sobering conclusion that there would be an uncontrolled decline in the world’s population and production capacities if existing economic growth trends were to continue. However, instead of pushing for sustainable ecological and economic stability, the guardians of the neoliberal regime continue to devise strategies for green, inclusive and sustainable growth. The latest in a series of such strategies is the European Green Deal, which ignored all warnings from environmental NGOs and intergovernmental forums that empirical data and evidence do not support the mantra of decoupling economic growth from the growth in greenhouse gas emissions and resource use. In search for an answer to why the political establishment continues to embrace growth as the ultimate goal of economic policies, and why modern society‘s obsession with material growth is so deeply entrenched, the paper critically questions the basic premises of neoclassical economic theory. Furthermore, the authors employ historical analysis in an attempt to understand the historical circumstances that enabled the emergence of capitalism, which can only be sustained through the growth of capital and which, as a class system based on the exploitation of human labor and the appropriation of the environment on an unimaginable scale, can only be reproduced by the concealment of the sources of growth. In its final part, the paper uses the feminist concept „absent from history” in order to detect if there was anything missing in the critical period of the transition from feudalism to capitalism in the late Middle Ages which could have altered the flow of Western history towards the formation of a more just society and mode of production.

Throughout the world, various versions of a Green New Deal have lately become the most politically visible attempt to overcome the gap between the urgency of the climate crisis and the insufficiency of current (and planned) measures to tackle it. Regardless of the concrete content of particular measures, the underlying principle of a GND is that the bundle of policies contained within are aimed at restructuring the economic system in a way that tackles the dual crisis of climate change and social inequality. This article deals with four different GND proposals that are the most relevant for the climate movement in Slovenia: two different GND versions from the USA, which are the foundation of the majority of debates among activists and academics, the European Green Deal put forward by the European Commission, and, as its counterweight, the Blueprint for Europe‘s Just Transition proposed by the Diem25 movement. The author analyzes the more or less explicit political strategies that form the basis of GND proposals and their understanding of the political barriers they have to overcome. By analysing the proposals as well as the debates they elicited, the author aims to provide an answer to the following questions: how do different GND proposals define the the problem they are trying to solve; who or what is responsible for the climate crisis; what are the timelines and the level of ambition; who are the agents tasked with making a GND a reality; and lastly, how do particular proposals position themselves in relation to capitalism.

Faced with environmental and ecological crises, as well as a crisis of living in a broader sense, we are constantly confronted with questions about acting and thinking for change, of breaking with the current state of affairs. Usually, we start from assumptions about the complex interplay of nature, humans and society, and generally do not question these seemingly self-explanatory starting points. With practice-oriented thought, we forget about the naturalized conceptual framework that persists in common sense. The lack of theoretical reflection is reflected in fragmented action, both at the level of environmental struggles as well as in the sphere which seeks to introduce conceptual considerations into these struggles so that they can better reflect on their actions. In light of these assumptions, the authors introduce their considerations with questions of the time understood as now, and the specific potential of this period where the reinvention of the subject presupposes its transformative dimension. The second part of the article deals with the issue of common sense and the transformation of the political into the post-political. In connection with the conceptual framing and understanding of man, the authors show that we are entering the environmental struggle with thinking that preserves the exclusion of both the subject who is to transform the existing relations and the space of the political in which this change is to be articulated.

The article attempts to resolve fundamental dilemmas that arise when (re)thinking the environmental crisis. Encountering this crisis is contradictory in itself, because it is un-reflected and trapped in alarmist discourse, preventing radical change. The author combines Spinozistic thought with newer ecological issues and theories. The author is interested in developing a conceptual apparatus that enables deeper and wider thought -not in an anthropocentric manner, but still avoiding the discourse of surrendering to fate and accepting the inability of man as a species to influence the biosphere. The immanent ontological basis is framed politically, through practice. The author develops his thought with the help of the concept of unnatural self-destructivism – a line by which one can think about ecology without the moral transcendent and without the danger of falling into the eco-fascist discourse of necessity and transfering sovereignty to professionals and institutions. The key will be a shift from essentiality to a critique of relationships that are toxic and destructive. Deanthropocentrism in thought works in a similar way to a process of decolonization of knowledge. The affirmation of nature and environment will be similar to the affirmation of slaves. This article has a similar purpose.

In the 21st century, we are not only confronted with a serious threat that the world around us will no longer be habitable because of our inappropriate ecological behavior, but we are also faced with the “perversion of the political”, which has a destructive effect on both the social and the natural world. Current environmental issues are directing us towards new possible alternatives aimed at replacing existing neoliberal policies which impact both the natural and social realms and increasingly also affect the sphere of the individual. This intervention in the sphere of the self is called psychopolitics, and it represents the disciplinary rule of neoliberal capitalism. The subject becomes depoliticized, alienated and removed from the process of decision-making and co-creation of the shared/collective world in which it is placed into. The subject’s task is to re-appropriate its area of appearance, to re-appropriate its voice, and at the same time to make sure that other actors also have the opportunity to co-create a world in which they reside together. Indigenous ways of life and indigenous people’s relation to the world can be one of the foundations that can help us understand the origins of environmental issues. At the same time, their stance can also offer us an alternative for transitioning towards a society that does not exceed planetary capabilities and is more friendly for the individual, the collective and the environment.

The article discusses the conceptual background of the anthropogenic dimension of climate change and its effect on a population’s socio-economic vulnerability and mobility. The effects of climate change will fundamentally affect core aspects of societies, leaving an impact on their fundamental values, lifestyles and management. Climate change will also result in the limited ability to adapt and reduced resilience of the population to environmental/climatic changes, as well as increased climate vulnerability. Migrations are one of the ways humans react to changes in their living circumstances. This article aims to shine a light on the understanding of global processes that are responses to climate change effects, as well as the existing state of inequality in the climate burden-sharing processes. Within the nexus of environment-climate-migration, the author offers a critical discussion of the established use of terminology and concepts such as »climate refugees«, while highlighting the background of the question of climate migration in international agreements, as well as in environmental and migration policies. Migrations that occur as a response to climate change effects are therefore expressed as a multilayered phenomenon and show how populations adapt to new environmental, societal, economic and political conditions. In its closing remarks, the article is focused on equitable and effective measures for addressing these migrations. The author touches on the ways in which developing countries are adapting to climate change, but also highlights the increased levels of climatic, social and economic vulnerability.

The author discusses the influence of climate fluctuations on the Roman state, ranging from the warm period in the time of its growth and development, to the significant climate fluctuations that happened during its first crisis and contributed to the fall of the western part of the Empire. Climate fluctuations themselves contributed to the factors that led to the fall of the Western Roman empire and coincided with internal factors that stemmed from contradictions within the Roman system. The end of the warm period was accompanied by migrations and civil wars which were exacerbated by climate fluctuations, because they led to hunger and epidemics. These climate fluctuations mostly weren‘t caused by human actions, although there could have been some impact from human activity due to intensive deforestation, which was a consequence of shipbuilding, and the growing size and number of towns and cities and industrial-scale crafts. The main drivers were the changes in solar activity, vulcanism and oceanic-athmospheric fluctuations, mostly north-Atlantic oscillation and southern oscillation (El Ni).

The author introduces us to the main ideas and concepts of Russian thinker Alexander Vasilievich Chayanov. Even today, Chayanov is an important reference in peasant studies and movements aroud the world. He wrote about the position of peasants within an economy that’s organized by capital, and the potential of the peasantry for social and political transformation. Van Der Ploeg reflects on the usefulness and potentials for translating Chayanov‘s findings and concepts into today‘s world. The text is a translation of the first chapter of Van Der Ploeg‘s Peasants and the Art of Farming (Fernwood Publishing, 2013).

In many parts of the world, “environmentally friendly hydropower” does not represent a solution but instead contributes to environmental devastation and increasing social inequality. Since natural environments are not detached from social contexts, an intersectional approach that takes into account class differences, gender inequalities, ethnic boundaries, age, disability, and other diversities that generate social inequalities is needed. Internationally, women are part of environmental justice movements and struggle against corporate exploitation that has damaging effects on local ecosystems and communities. One of the most important local protests led by women in the region of the Southeast Europe are the “brave women of Kruščica” from Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the local population prevented international investors and corporations from building hydropower plants in the region. In addition to Bosnia and Herzegovina, women are also playing a crucial role in environmental activism in Slovenia. Nevertheless, the experiences of women across the world show that environmental activism is not free from patriarchal inequalities and the desire to make women conform to established patriarchal templates.

In order to illuminate the environmental struggle in Slovenia, the article focuses on two concrete cases – the fight against new hydro plants on the Mura and Sava rivers, as well as the fight against waste incineration in Anhovo, a place already tainted by asbestos. Both cases confirm that the protection of nature and the environment are primarily conducted by non-governmental organizations. The author outlines several methods for attempting permanent interventions in nature that are being employed by private and public capital in conjunction with state institutions. Following the dictates of governing politics, the protection of the environment and nature is increasingly seen as an administrative obstacle and not as a constitutionally protected category.

“And so Life Brought Me to the Rivers, Even Though I Always Wanted to Just Be a Farmer.” An Interview with Andreja Slameršek

(

Andreja Slameršek is one of the most prominent names when it comes to current environmental struggles in Slovenia. For years, she has been using her experience, skills and knowledge to resist the devastation of rivers and the natural habitats that surround them. In the interview, she speaks about the degraded environment she grew up in, the importance of local engagement, her working experience in institutions, the cooperation of politics and capital and its impact on environment degradation, and the importance of legal stuggle.

Rok Rozman is one of the most prominent environmental activists of the new generation. His actions are strongly embedded in the local environment, but also flow across the Balkan’s borders, just like the rivers he is protecting. In the interview, he speaks about his roots, connection with nature, sports career, and the direct actions he organized in order to protect free-flowing rivers. He also shares a few interesting facts about birds and fish.

The article has two main goals -firstly, the author presents the fundamental international legal principles regulating the use of transboundary aquifers. These principles are a mutatis mutandis reflection of the principles regulating non-navigational uses of international watercourses. Secondly, the author takes the use of the waters of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers as an example to highlight the different ways for achieving adherence to the principles mentioned above, tackling the issue not just from the point of view of the law regarding transboundary aquifers and international watercourses, but the entire system of international law. The author argues that cooperation between states is crucial for the effective implementation of the principles regarding the use of transboundary aquifers and international watercourses. Cooperation in itself is an obligation of states under customary international law. Where cooperation is lacking, states, individuals and non-governmental organisations may utilize mechanisms within international environmental treaties and international human rights law. Regarding the latter, the article presents the recent developments in the practice of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which could have important consequences in Europe if it is to be followed by the European Court of Human Rights.

The article is divided into three parts. In the first part, climate justice is defined as an anti-systemic struggle for a just and dignified life for all on an ecologically diverse and preserved planet. This means building a movement based on solidarity, inclusiveness and comradeship that is aware of the intertwinement of the climate crisis with the other problems facing the world and their common origin in the existing system. In the second part, the author substantiates the definition above by explaining why capitalism is inherently environmentally destructive. The concept of the four core climate inequalities is also discussed, namely the inequality in the causation of climate crisis, the inequality in the effects of climate climate change and the ability to cope with them, the inequality in bearing the expenditures and benefits of transitioning to a low-carbon society and last but not least, the inequality in the treatment of nature. These four inequalities are broken down further into global, national and gender categories. Finally, they are applied to the Slovenian context. Stemming from the critique of capitalism and the four climate inequalities, the third part of the article emphasizes that the struggle for climate justice is an international, anti-systemic, anti-colonial, workers‘, feminist, migrant, anti-speciesist and conservationist struggle. In turn, these struggles are also climate struggles. The article also addresses the question of the relationship towards the state. The bourgeois state has many clear limitations, but it cannot be ignored in the wake of climate breakdown. A “movement-party”, where a party merely represents an extended arm of the movement in parliament, is proposed as a sensible way forward. In more concrete terms, the demands of the Slovenian movement Youth for Climate Justice, as well as their connections with various movements during the September 2019 protests, are presented as a relatively suitable and tangible step towards putting climate justice into practice. However, protests are not enough – the movement must support the struggles of other organizations and slowly but steadily build a „parallel“, solidarity-based, worker- and nature-friendly economy. In addition, the movement cannot develop and exist without educated members – movements stand or fall on education. Finally, a possible (additional) way of realizing climate justice in practice is demonstrated through community-based renewable energy projects.

V preteklih dneh smo lahko zasledili številna pisma podpore in druge načine izražanja solidarnosti s stavkajočimi avtobusarji in avtobusarkami skupine Arriva. Izrazi podpore so prihajali s strani različnih sindikatov in drugih progresivnih, delavsko usmerjenih skupin. Podpore okoljevarstvenikov ni bilo mogoče zaslediti. Kljub našim prizadevanjem se to ni zgodilo. Nismo razočarani, skupnega odziva objektivno gledano niti nismo pričakovali. Manko podpore okoljevarstvenikov razumemo kot rezultat preteklega, bolj ali manj sovražnega in nasprotujočega delovanja delavskih in okoljskih organizacij. Za rešitev teh težav in vzpostavitev prijateljskega sodelovanja med delavskimi in okoljskimi organizacijami bomo morali postoriti še marsikaj. Z namenom prispevati k temu projektu bomo v nadaljevanju predstavili en splošni, tri kratkoročne in en dolgoročni argument, zaradi katerih bi morale vse progresivne okoljevarstvene organizacije izraziti solidarnost in podporo stavkajočim delavcem in delavkam skupine Arriva. Stavka ima mnogo več opraviti z okoljskim vprašanjem, kot se na prvi pogled zdi.

A Letter to the Union of Professional Firefighters of Slovenia and an Invitation to the Together for Climate Justice Protest

(

Okoljska katastrofa in njen vpliv na gasilstvo

Okoljska kriza se danes širom sveta kaže v najrazličnejših oblikah – segrevanje ozračja, skrajni vremenski pojavi, otoki plastike sredi oceanov, izumiranje živalskih vrst, vedno večji in pogostejši gozdni požari itd. Že vsaj trideset let znanost stoji za trditvijo, da je velik del podnebnih sprememb antropogen, torej rezultat človeških dejavnikov. A ne glede na to smo ravno v zadnjih tridesetih letih v zrak spustili več emisij ogljikovega dioksida kot v prejšnjih dvesto letih, ob tem pa pridelali največ plastike, izsekali največje površine gozdov, ogromno živih bitij pa pripeljali na rob (če ne že čez rob) izumrtja.

V času izrednih razmer zaradi koronavirusa smo pri Mladih za podnebno pravičnost spontano in iz prepoznavanja potrebe po novih vsebinah organizirali serijo desetih pogovorov z več kot dvajsetimi aktivisti, strokovnjaki in praktiki iz Slovenije in tujine. Spodaj navajamo seznam s kratkim opisom in literaturo, na katero se lahko bralstvo obrne. Želimo si, da bi kompendij služil kot pripomoček za skupinsko samoizobraževanje na področjih, ki so v Sloveniji izjemno zapostavljena, v zametkih ali še neobstoječa.

In face of the health consequences, and when seeing the impact of weapons on the living planet, one could think it’s not relevant to care about ecology when there’s war, but Freedom fighters of North-Eastern Syria’s Autonomous Administration show us there is more to war and ecology than what it seems at first. Let’s dig into the third pillar of the Rojava revolution, and see how it connects to the struggle for freedom.

The understanding of ecology that is given to us by capitalist modernity, through ads, government campaigns and liberal culture, is usually to take care of the environment in an individual, immediate way. For example, by not throwing trash on the floor, and instead putting it in the bin, so that it gets (maybe) recycled later. Or by shutting all the lights off when going to bed.

Sunce se još nije bilo uspjelo uspeti preko horizonta, dok je bus u kojem sam se vozio ispustio hidraulični zvuk kočnica u malenom selu Villa Ojo de Agua, na jugu argentinske provincije Santiago del Estero. Nisu prošle više

od dvije minute (koliko je i trajalo iskrcavanje jedne osobe iz autobusa) i već sam se sa svojim turističkim bekpekom osvrtao na majušnoj stanici, ne bih li pronašao nekoga za priupitati, na svom krnjem španjolskom, kako stići do UNICAM-a, jednog od punktova seljačkog društvenog pokreta MOCASE, nastalog prije trideset godina.

A Transdisciplinary Study of Bioremediation Practices Used in Solving the Issue of Contaminated Areas in Slovenia

(

V slovenskem prostoru ob omembi gliv in gob najprej pomislimo na hrano. Vsekakor je hrana eden od načinov uporabe gliv, vendar pa nam ti organizmi ponujajo tudi številne možnosti rabe v zdravstvu (preventiva in kurativa), kmetijstvu (pridobivanje insekticidov in gnojil), pri protipoplavnih ukrepih (absorpcijska polja), dekontaminaciji onesnaženih voda in zemljin, predelavi in razgradnji različnih odpadkov in izdelavi trajnostnih materialov, če naštejemo zgolj nekaj izmed njih. Imajo tudi pomembno vlogo pri vzdrževanju ekosistemov (kroženje snovi s pomočjo razgradnje kompleksnih molekul, povečevanje rasti kopenskih rastlin z mikorizo) in s tem povezano vlogo pri uravnavanju podnebja.

The author presents the beginnings and inner workings of the Zero Waste Žalec grassroots movement, which began in Žalec in 2018. The small collective is inspired by Bookchin‘s idea of Free nature. The collective works primarily in the sphere of information dissemination, and leads by example of good practices. The movement is nested within its locality and takes the needs and desires of the local population into account.

Opening Pandora’s Box: An Attempt at Writing a History of Slovenian Environmental Movements

(

The author outlines a history of environmental movements in the last decade of Yugoslavia through a narrative influenced by personal experiences. In the 1980s, several initiatives took stances against industrialization, warned about pollution and opened the question of energy production and provision (with a special emphasis on nuclear power). Environmental movements also played an important role in the processes of democratization and the development od political culture.

Pandemija koronavirusa je vzela že številna življenja in negotovo ostaja, kako se bo razvijala v prihodnosti. Medtem ko se delavci in delavke v zdravstvu in temeljni družbeni preskrbi v prvih vrstah borijo proti širjenju virusa, skrbijo za bolne in zagotavljajo, da najnujnejše dejavnosti tečejo naprej, se je velik del gospodarstva ustavil. Mnoge zaradi trenutnega stanja prevevajo tesnoba, bolečina ter skrb za najbližje in skupnosti, del katerih smo, je pa to tudi čas, da skupaj ponovno osmislimo in sooblikujemo našo skupno prihodnost na planetu.

The Tragedy and Farce of Social Bodies in the Ideological Perspective of Information Technology

(

The article discusses a series of events pertaining to the global economic recession (2007–2014) and analyzes the role of current technologies, including social media platforms, in the new aestheticization of the origins of social groups involved in revolt. The author employs historical analysis in order to establish an argument for the inevitability of the repetition of world-historic facts, paralleling it with Marx‘s well known passage: “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”. The article deploys Benjamin‘s introduction and usage of the term degeneration [Entartung] in his critical analysis of artistic and political practices. The second part of the article addresses the issue of culture industry and mass media and how they engendered “postdemocracy [that] erased true politics”, as succinctly put by Rancière. However, postdemocracy did not foresee the collective power possessed by contemporary technologies of social media. These technologies played a crucial role both in the uprisings against the measures to save financial capitalism and elites, and the rise of Donald J. Trump to the presidency. The concluding remarks return to the article‘s outset by stating that the first (leftist) usage of social media and related technologies has tragically failed in its ambitions for radical emancipatory change. On the other hand, the second (right-wing) repetition was indeed successful in achieving its particular goals.